The social clubs of London — real or imagined — have often featured in popular works of fiction. It was, for example, at the Reform Club (‘an imposing edifice in Pall Mall’ patronised by ‘the princes of English trade and finance’) where Phileas Fogg scandalously announced over a game of cards that he would travel the world in only eighty days. Likewise, Messrs Wooster, Twistleton and Psmith have spent many memorable evenings at the slightly less exalted Drones Club (‘if you stop short of smashing the piano, there isn’t much that you can do at the Drones that will cause the raised eyebrow and the sharp intake of breath’). In stark contrast, however, lies the Diogenes Club (according to Sherlock Holmes, ‘the queerest club in London’ with ‘the most unsociable and unclubbable men in town’).

The Bengal Club — with all its exclusivity and eccentricity— has similarly been a passive participant in many a literary plot penned by many a celebrated writer. Below is a selection of novels, short stories and the odd non-fiction work referring to the Club.

The prolific British writer Rumer Godden — winner of the Whitbread Award and author of Black Narcissus (adapted into an Oscar-winning film) — ranks first on our list. The primary reason is the flattering reference in her novel The Dark Horse, set in Calcutta: ‘The Bengal Club had the best food east of Suez, especially their spiced hump of beef and a certain Greek pudding made of sago, palm sugar and coconut. It was also renowned for its cellar and its custom of a glass of Madeira after luncheon.’

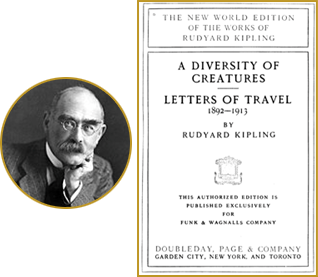

The first Indian-born writer to win the literature Nobel did not often have pleasant things to say about the land of his birth. In The City of Dreadful Night, Kipling refers to the ‘stink’ and ‘stench’ of Calcutta which ‘comes in gusts into the corridors of the Great Eastern Hotel’ and ‘swirls round the Bengal Club.’ However, in his travelogues, Kipling paid the Club what would appear to be a generous compliment (by his choleric standards): ‘In the stately Hongkong Clubhouse, which is to the further what the Bengal Club is to the nearer East, you meet much the same gathering, minus the mining speculators …’

Our second non-fiction entry is W Somerset Maugham’s A Writer’s Notebook, published in 1949. Unfortunately, the reference to the Club is far from charitable. During lunch with the writer, the Prince of Berar had apparently told him: ‘In the Bengal Club at Calcutta they don't allow dogs or Indians, but in the Yacht Club at Bombay they don’t mind dogs; it’s only Indians they don't allow.’

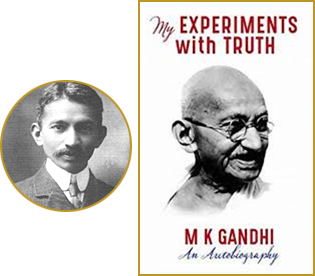

Perhaps the most infamous example of the racial discrimination mentioned by Somerset Maugham was the treatment of Mahatma Gandhi at the Club. In his autobiography, Gandhi wrote: “I became acquainted with Mr. Ellerthorpe, a representative of The Daily Telegraph. He invited me to the Bengal Club, where he was staying. He did not then realize that an Indian could not be taken to the drawing-room of the club. Having discovered the restriction, he took me to his room. He expressed his sorrow regarding this prejudice of the local Englishmen and apologized to me for not having been able to take me to the drawing-room.”

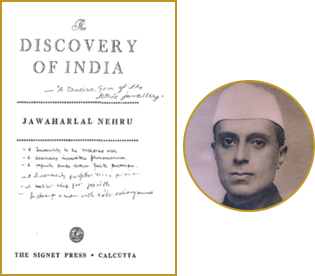

Continuing on the same theme, Nehru said of the Bengal Club in The Discovery of India: “The exclusion of non-Europeans is far more a racial affair than a justifiable means for people with cultural affinities to meet together in their leisure moments for play and social intercourse, without the intrusion of other elements. For my part I have no objection to exclusive English or European clubs, and very few Indians would care to join them; but when this social exclusiveness is clearly based on racialism and on a ruling class always exhibiting its superiority and unapproachability, it bears another aspect.“ Eventually, in independent India, Nehru was entertained to lunch by the club's president and committee members.

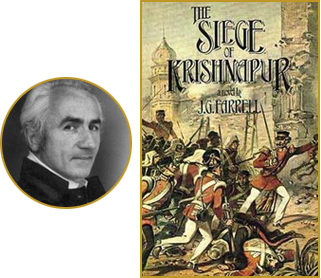

In JG Farrell’s The Siege of Krishnapur, winner of the Booker Prize in 1973, Fleury, a young Englishman with a poetic bent, is said to have ‘cornered some poor devil in the Bengal Club and read him a long poem about some people climbing a symbolic mountain.’ Farrell’s novel was inspired by the Revolt of 1857 and is partly set in Calcutta

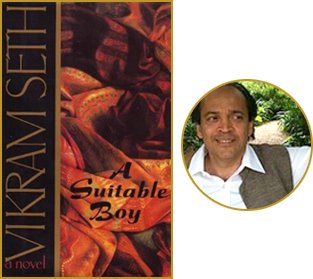

In Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy, widely regarded as one of the greatest Indian novels in the English language, it is said of Mr Justice Chatterji of the Calcutta High Court: ‘He would…go to the Bengal Club, where he would sit on a high chair and drink as many whiskies as he could.’

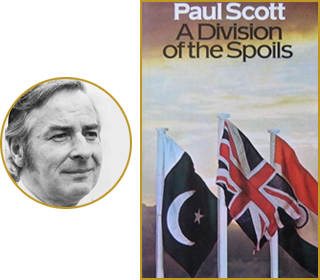

In A Division of the Spoils, a 1975 novel set during the Partition of India and written by Paul Scott (another Booker Prize-winning author), the Bengal Club finds multiple mentions. Somewhat unflatteringly, the Club is described as a place frequented by Englishmen ‘living in the nineteenth century’ who ‘looked like dying of apoplexy’ after learning that Indian independence was fast approaching.

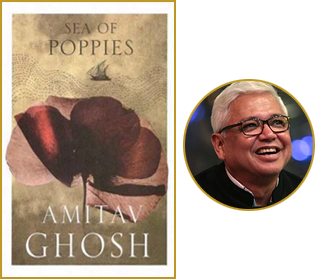

In Amitav Ghosh’s Sea of Poppies, shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 2008, Mr Justice Kendalbushe dines at the Bengal Club with an acquaintance and discusses a proposal concerning a slightly delicate matter.

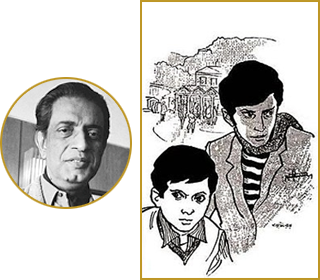

The Bengal Club has the distinction of being namedropped in two short stories by the great Bengali filmmaker and writer Satyajit Ray. In Bosepukure Khunkharapi (English title: ‘The Acharya Murder Case’), the legendary detective Feluda makes enquiries about a character and learns that his brother is a member of the Bengal Club. In Ashamanja Babur Kukur (English title: ‘Ashamanja Babu’s Dog’), a Parsi gentleman, Piloo Pochkanwalla, visits the Bengal Club and narrates an incredible anecdote about the story’s canine protagonist.

The novel Voices in the City, by the acclaimed writer and two-time Booker Prize nominee Anita Desai, features a character who lunches at the Bengal Club with an English friend (‘he couldn’t, of course, be a member of that club himself’). The novel, published in 1963, was Desai’s second and deals with the life of the middle-class intellectuals in Calcutta.

The British detective novelist H.R.F. Keating was best known for his comic Inspector Ghote detective series. In one of these books, Ghote is invited to the Bengal Club. Ghote’s host tell him a probably apocryphal story: “Now here is a custom of the Bengal Club that I fear I must explain to you. A custom established, I would venture to guess, in the full flush of the British days, and preserved by tradition ever since. Between the first course at luncheon here and the fish… we always have served, irrespective of what has gone before, irrespective of what is to come after … an omelette.” Nevertheless, the Club was, and continues to be, famed for its omelettes.

In Shey Shomoy (English title: ‘Those Days’), a historical novel by the noted Bengali writer Sunil Gangopadhyay which won the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1985, the character Nabin Kumar is described as having sold his land to the Bengal Club. The character is believed to be a fictionalised depiction of Babu Kali Prasanna Singha (see the ‘History of the Bengal Club’ section on this website).

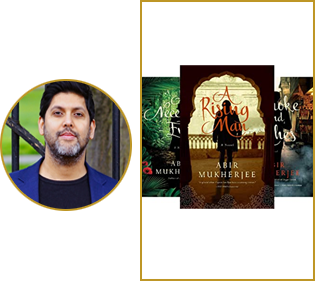

In the Wyndham and Banerjee series of detective novels by the British-Indian writer Abir Mukherjee, set in colonial Calcutta, the Bengal Club makes an appearance in three books: A Rising Man, A Necessary Evil and Smoke and Ashes. The references range from the picturesque (‘his face as long as the bar at the Bengal Club’) to the poignant (‘I may be a prince, but the colour of my skin precludes me from entering that august institution’).

Below is as inexhaustive list of other work referring to the Bengal Club

(both fiction and non fiction)

The above images are taken either from the Wikipedia pages corresponding to the titles of the books and authors, or from Wikimedia, excepting the images of Anita Desai (from a webpage of the British Council), Abir Mukherjee (from the author’s website) and The Dark Horse, A Writer’s Notebook, Voices in the City and the Wyndham and Banerjee books (all from Amazon.com). The Bengal Club believes that its use of the above images falls within the fair dealing exception under section 52 of the Copyright Act 1957. If you would like to communicate with the Club in this regard, please email us at secretariat@thebengalclub.com